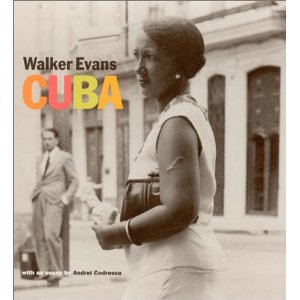

As I wrote on TGBSW yesterday (The Art of Travel), art is often the best way to begin to get to know a place. A little over a year ago I wrote a paper on Walker Evans’s time in Cuba that I thought I would share as an example of how the eye of the artist can enlighten the soul of a place.

As I wrote on TGBSW yesterday (The Art of Travel), art is often the best way to begin to get to know a place. A little over a year ago I wrote a paper on Walker Evans’s time in Cuba that I thought I would share as an example of how the eye of the artist can enlighten the soul of a place.

———–

In May of 1933, American photographer Walker Evans journeyed to Cuba to photograph scenes for a book on the dire political situation there. Carleton Beals, considered a “radical” journalist, had written an expose, Crime of Cuba, on the regime of Cuban President Gerardo Machado and the complicity of the United States in the oppression of the Cuban people.i Beals’s publisher, J.B. Lippincott, was looking for a photographer to illustrate Beals’s book and commissioned Evans to do the job. Lippincott was likely hoping Evans’s photography could put a human face to the Cuba that Beals’s polemical and rhetorically excessive style tended to caricature.ii Evans, however, was a curious choice given his perspective on the role of photography and proved not the best choice for a collaboration that required the manipulation of viewpoint. While Lippincott’s choice of Evans did not prove to be the best for Beals’s book, it does present us with some of Evans’s best work that presages his later photographs for the Farm Security Administration immortalized in James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.iii

Evans’s career in photography began as a compromise. For Evans in 1927 New York, photography was “a substitute for other things, for writing.”iv Evans’s “burning desire to be a writer”v imbues his photographs with a narrative depth that transcends mere documentation and rejects mere aesthetics.

It may have been that burning desire to be a writer that oriented Evans towards collaborating with writers, such as Beals. Evans’s first such collaboration occurred in 1930 on poet Hart Crane’s The Bridge and demonstrated Evans’s “respect for the specific and the complementary in both photography and the written word.”vi For Crane’s poetry, Evans’s New York abstractions indeed supplied images that were perfectly complementary.vii When people speak of the lyricism of Evans’s photography, this is the period that most comes to mind (Fig. 1).

Unlike Evans’s more successful collaborations with Crane and later with Agee, Evans’s photographs did not always mesh well with Beals’s writing, and Evans had managed to negotiate an important condition for the assignment that may have made all the difference: he insisted on choosing the photographs to be included and the order of their appearance.viii

Despite what proved to be his work’s incompatibility with Beals’s purpose, Evans was not without an understanding of the dire situation in Cuba under Machado, which would only worsen later in 1933 under another U.S. supported despot: Fulgencio Batista.ix He feared for his own safety and was afraid that his photos would be seized by the Cuban government.x Evans left Cuba with 400 negatives of which 31 made it into Crime; Evans left 46 prints behind with Ernest Hemingway, who Evans met and befriended while in Cuba.xi

Despite Beals’s good intentions, what his book leaves us with today is Evans’s photographs, which are anything but polemical or excessive. They demonstrate a diversity of the human experience that was the Cuban citizenry and its culture in 1933. The heated arguments among Beals, Lippincott and Evans over what photographs to include had to have been something to behold, but it was solely Evans’s choice.

If a photograph is a two-dimensional simulacrum of reality as presented through the eye of the photographer, photos as unedited reality don’t exist as the reality is necessarily edited the moment the picture is captured. What is left out can completely transform the subject matter. But unlike a painter or sculptor or even writer, the street photographer is at least limited to what he or she finds to commit to film. Evans understood well the importance of manipulation of the frame to tell a story but also understood the social and artistic responsibility related to such discretion. Maybe this was one of the sentiments Evans was conveying with his cryptic statement about thinking himself mad when contemplating the possibilities of the photographic medium.xiii

But there is a difference between edited and slanted, an important distinction that Lippincott discovered a bit too late. For Evans, the camera “was simply a convenient mechanism for collecting ideas, icons, and anecdotes”xiv and less of a tool for advancing a particular ideology or shaping a worldview.

Balcony Spectators (Fig. 2) is a prime example of how what is left out of the frame can potentially transform the story being told. What is the spectacle taking place beneath the gaze of the balcony denizens? Whether a food riot or a parade changes the narrative. While Evans no doubt recognized the limitations of the photographic plane, he ultimately trusted his eye and his ability to capture the whole story in frame. In this situation, we see in the calm demeanor of this multi-generational family that there isn’t much of interest below. These are spectators of life in Cuba and as such were the necessary conduits for the story Evans was attempting to tell as it naturally unfolded, not the story mandated by the text of a book or the dictates of a publisher.

And Evans did not avoid scenes of abject poverty, such as Woman and Children (Fig. 3). Still powerful and heart-rending today, scenes such as that in Woman would become all-too familiar subject matter to Evans during his time working in Depression-era America. Although Beals would likely have preferred a title such as Impoverished Woman Watching Her Malnourished Children Die on the Street Due to the Oppressive Policies of the Despotic Cuban Government Callously Supported by the United States, Woman, along with a few other photos, came closest to fulfilling the theme of Beals’s book. Most importantly, Evans knew that such a picture needed nothing further to convey the human tragedy beheld.

As was the case with many artists during this period of world history, Evans was not blind to the catastrophic tale unfolding everywhere, including Cuba and the United States. But, then as now, hope and the indomitable nature of the human spirit are important forces in a world presenting an uncertain future. What we see in Evans’s photographs from Cuba is a testament to human dignity and fortitude when faced with the most challenging of circumstances. Evans saw beauty in a world where others saw only corruption and decay, which can be viewed as an important legacy in an era that saw only the futility of living.

Moving from early photographic abstraction with a touch of surrealism to a more documentary style, “Evans’s work…constitutes a reaffirmation of what has been photography’s central sense of purpose and aesthetic: the precise and lucid description of significant fact.”xvi But Mora and Hill’s pronouncement presents Evans’s work as overly concerned with factual aspects and appears to see the documentarian approach as incongruous with creating something artistically worthy as further observed: “Perhaps the ultimate demonstration of Evans’ wit was his delight in passing himself off as a documentary photographer, nay, even a photojournalist, and while enjoying his charade producing some of the most profoundly lyrical images of our century.”xvii

That the two impulses in photography are not incompatible becomes profoundly evident in Evans’s work in Cuba. As Andrei Codrescu deftly observes, “[t]he only difference between the early Evans, the aesthete, and the later Evans, the social documentarian, is that the foreground and background exchanged places: the aesthete had the ‘story’ in the background, while the documentarian put the story up front. In Cuba, the two Evanses were both present, though the aesthete was still in charge.”xix

—————————–

End Notes:

i John Harris, ed., Walker Evans, Cuba (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2001), 7; see also, Carleton Beals, Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carleton_Beals).

ii Andrei Codrescu, “Walker Evans: The Cuba Photographs,” in Harris, 14.

iii Walker Evans, Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walker_Evans).

iv Leslie Katz, “Interview with Walker Evans,” Art in America, March-April 1971, as quoted in Giles Mora and John T. Hill, Walker Evans: The Hungry Eye (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated, 1993), 13.

v Mora and Hill, 14.

vi Mora and Hill, 28.

vii Of these photos, Evans would later comment that he had come to find them too romantic. See Mora and Hill, 28.

viii Mora and Hill, 78.

ix Fulgencio Batista, Wikipedia, (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fulgencio_Batista).

x “Ernest Hemingway and Walker Evans: Three Weeks in Cuba,” Indepth Art News, Absolutearts.com (http://www.absolutearts.com/artsnews/2005/12/23/33558.html).

xi “Three Weeks in Cuba,” Indepth Art News.

xii Susan Berhard, Wellness Writer, (http://bipolarwellness.blogspot.com/2009/09/wellness-activity-using-my-right-brain.html).

xiii Szarkowski in Mora and Hill, 68.

xiv Mora and Hill, 7.

xv Harris, 36.

xvi John Szarkowski, Walker Evans, cat. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1971) as quoted in Mora and Hill, 10.

xvii Mora and Hill, 7.

xviii Likeyou, the art network, (http://www.likeyou.com/de/node/12347).

xix Codrescu in Harris, 26.